8: The Trinity Birch

This episode continues the focus on my Dad's life and his work and is a chronological extension of events covered in episodes 5 and 6. Although the focus features my family's life in the 1960s and 1970s, the narrative stretches back to events in 17th century Dublin before finishing up in more contemporary times and the legacy my Father left behind.

The Trinity College Birch

Sometime around 1965 a call was placed to the Agricultural Institute in Kinsealy where my Dad worked. The inquiry originated from the Trinity College Botanic Garden and the caller was looking for emergency help. He or she, the name is unknown to me, needed a plant rescue. The plant in question was a tree known as the Trinity College Birch or to go full plant nerd on you: Betula utilis jacquemontii ‘Trinity College’.

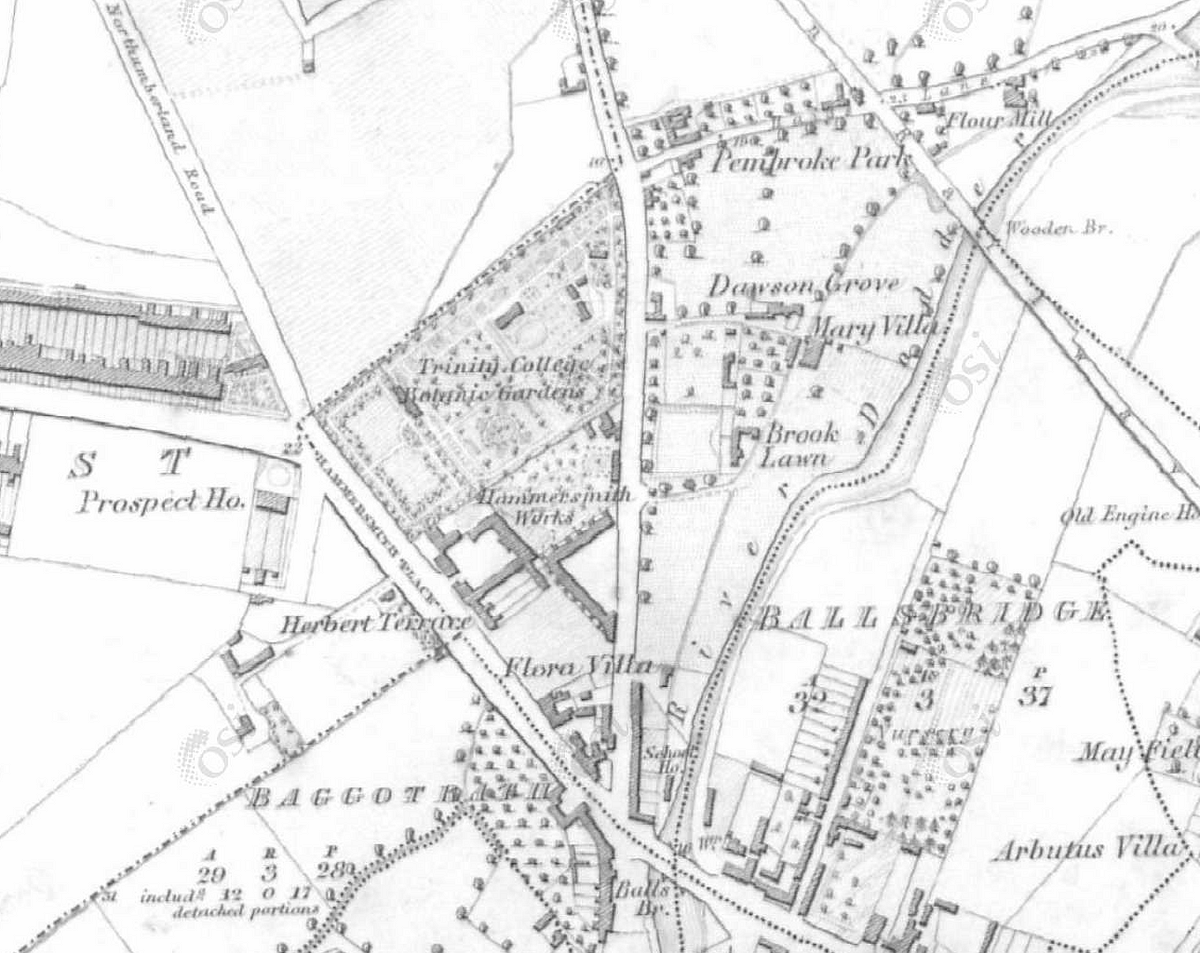

What actual peril was this tree in? The answer was, dire peril. Not from disease or some other naturally occurring event, rather it was simply the ground that the tree was rooted in. The Trinity College Botanic Garden was moving from it’s leased land in Ballsbridge about a mile and a half South East from the main college campus. The lease had been taken out in 1806 for 175 years at an annual rent of 15 guineas per acre. A guinea is an odd unit of currency, usually used in the purchase of luxury goods and translates, in modern terms to 1 British Pound and 5 pence. Factoring in inflation over the past 200 years, the annual rent amounts to £94.85 or €109.14. Now, if you know anything about Dublin real estate, Ballsbridge is one of the pricier locations in the city and while 1960s Ireland was not actually booming the economic possibilities looked significantly brighter than previous decades.

Clearly some enterprising individual had looked at the old garden sitting on 6 1/2 acres of prime Dublin real estate and realized a far greater yield could be achieved if the site was repurposed. There was still some 15 years to run on the lease before a renegotiation would take place with the landlord at a significantly steeper price. How all this actually played out is unknown to me, but clearly the administrators at Trinity College were incentivized to relinquish their lease early. It wasn’t the first time that Trinity had moved it’s Garden.

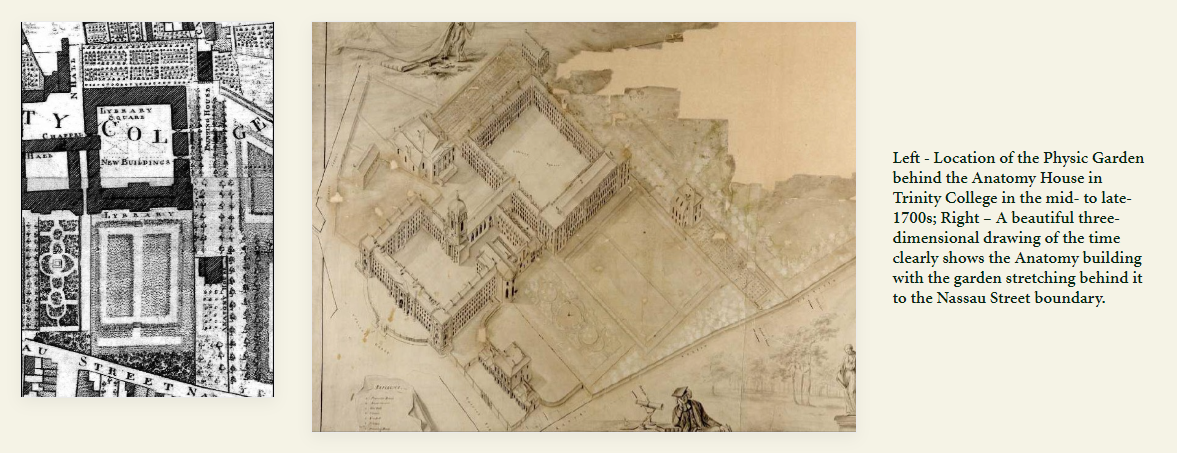

The original garden was sited on the main college campus in 1687 and was created not out of a love for botany, rather it was medicine that was the impetus, as 17th century physicians needed access to a good collection of plants to make their medications and so it was known as a physic garden rather that the later botanical. The first incarnation of the physic garden was replaced with the college’s newly built anatomy house in 1711 and the garden was re-sited between the new building and Nassau St. It seems the garden was poorly maintained and at times was used by the anatomy laboratory as an offal dumping ground. Unsurprisingly, this disturbingly, unhygienic approach to the disposal of human remains caused a gruesome rodent problem.

While the Physic Garden does not seem to have been a high priority with the medical school, the professors of botany began a campaign for a new space. The effort paid off and a new botanical garden was established at Harold’s Cross, however it was poorly funded. It wasn’t until the turn of the century that a new site of 8 acres was leased at Ballsbridge, creating a properly funded location in 1806.

For the next 160 years the garden and it’s property were enhanced, but nothing is forever and by the 1960s, economic forces were driving Trinity to relinquish it’s lease early. The garden was to be relocated once again, this time to a property in Dartry, 3 miles directly South from the main campus. The change in location would have been no small undertaking, moving plants is never easy, they are living organisms and are sensitive to disturbance. Then there is the matter of cost, scale and likely success when moving mature trees and here is where my Dad came in.

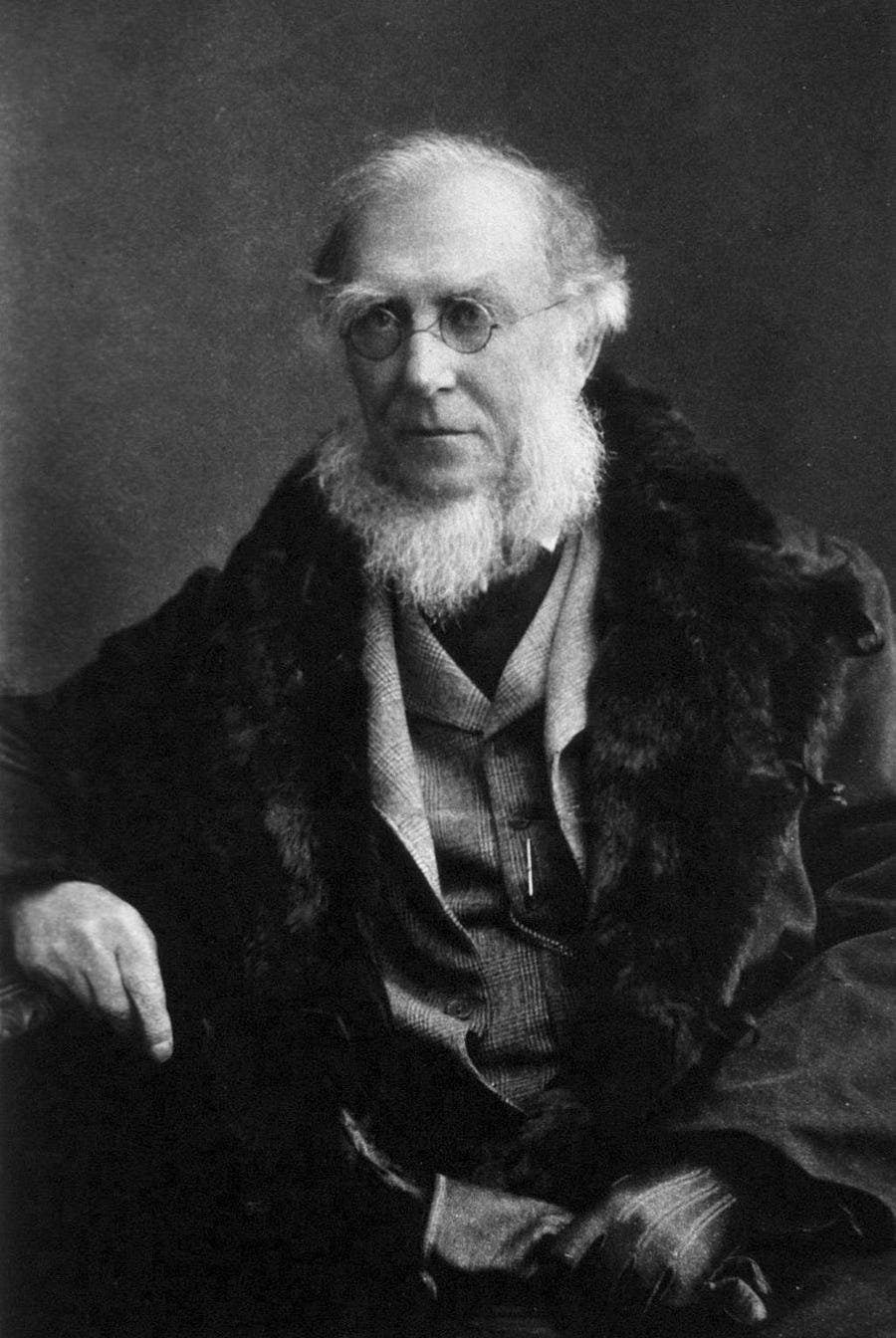

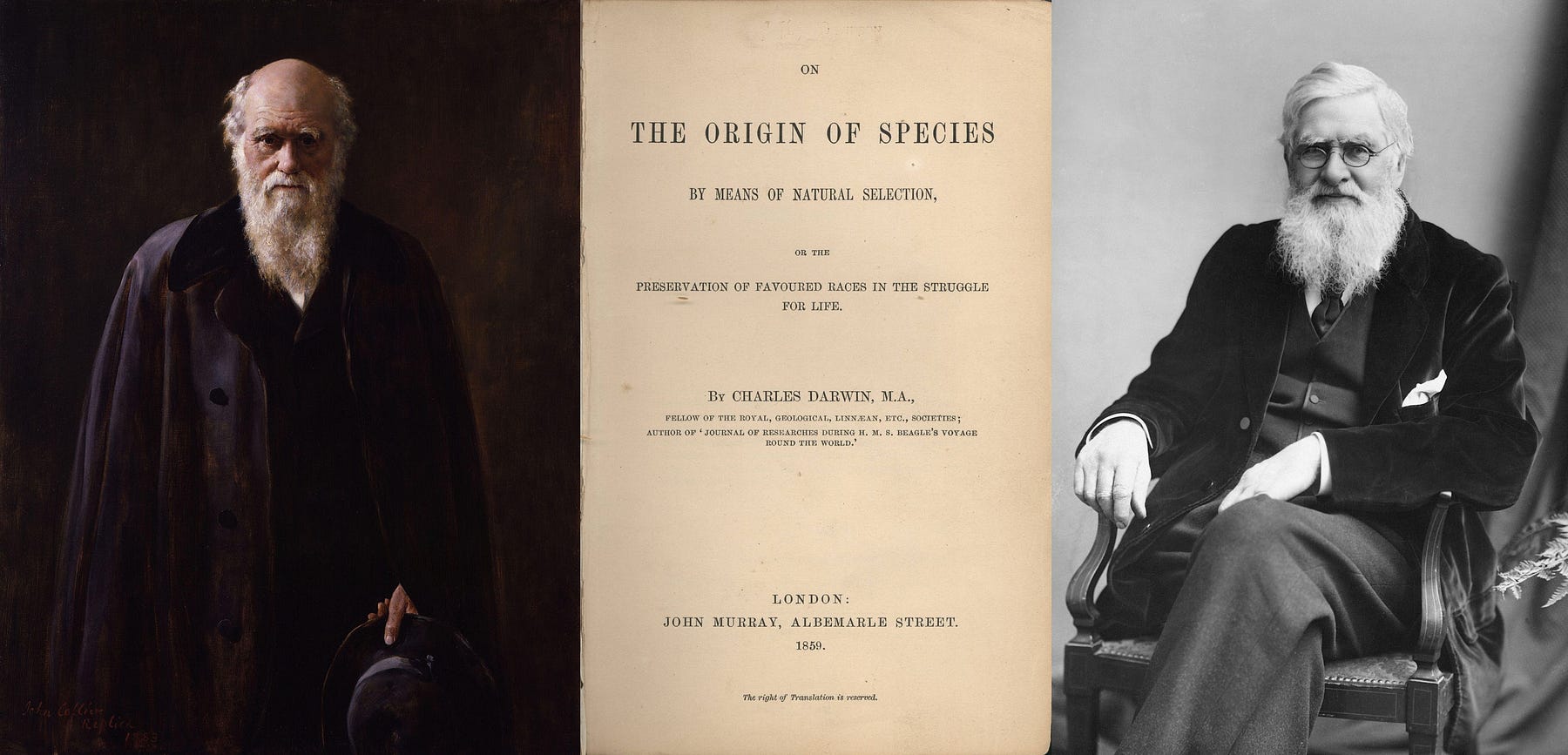

The Ballsbridge garden had a mature birch which possessed intensely white bark. The tree had an important association for the garden, it had been grown from seed sent from Joseph Hooker of the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew. Hooker was a seminal figure in the world of botany and also happened to be a close friend of Charles Darwin. The two men had become acquainted when Darwin asked for assistance in the classification of plants he had gathered on his famous Beagle voyage, an experience which was foundational to his book, On the Origin of Species, which would introduce evolutionary biology to a broader public.

The two men would become lifelong friends and Hooker was an important sounding board for Darwin as he labored over what would become the theory of evolution, indeed Hooker was key to establishing Darwin as the father of evolutionary biology. A strong case could be made that Alfred Russel Wallace should have partial claim to the theory of evolution, an idea he independently articulated in a paper on natural selection sent to Darwin in 1858, one year prior to the publication of the Origin of Species. Hooker, knowing that his friend Darwin had priority in understanding natural selection, moved to protect his friend’s legacy. At a Linnean society meeting, he presented Wallace’s paper accompanied by notes from Darwin in addition to correspondence which established Darwin’s priority. The publication of Darwin’s seminal work the following year would cement his reputation and consign Wallace to historic obscurity.

While Hooker would become a key defender of Darwin’s theory in the debates following the publication of the Origin of Species, he also carved out an impressive career in the botanic world. Over his long life, Hooker, made extended trips to some of the more remote corners of the globe and identified, gathered and classified previously undocumented plants. One of these trips, in the mid 19th century, brought Hooker to India and the Himalayas, where he came across what would become known as the Himalayan birch. He gathered seed from the tree and it was this seed that he sent to the curator of the Trinity Botanic Garden some 30 years later in 1881. The seed was successfully germinated and a tree was planted which produced strikingly white bark which differed from other progeny grown elsewhere from Hooker’s seed collection. It was a clear example of a cross generation mutation central to Darwin’s ideas on evolution.

Some 80 years after it’s germination, the mature tree with it’s striking white bark was slated for destruction, bulldozers were to clear the garden which was to become Jury’s Hotel now called The Ballsbridge Hotel. Transplanting an 80 year old tree was apparently not considered, the expense would likely have been excessive and the likelihood of successfully moving a mature, deeply rooted tree was limited. I don’t know if seed had been harvested from the tree, but if so, there was no guarantee that the next generation would have produced the same gleaming white bark, both Darwin and common sense tells us, children are not duplicates of the parent. Given time was short and seed unreliable, attempts had been made to propagate the tree through cuttings, apparently that effort had failed and so a call was placed to the Horticultural Department of the Kinsealy Institute where Dad worked.

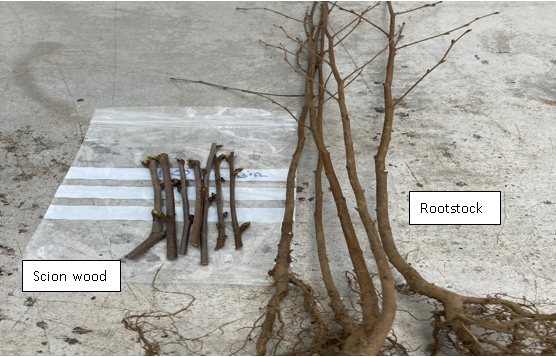

When a species is difficult to propagate by cuttings, it makes good sense to try grafting, the required variety onto an established rootstock of a compatible species. That involves, growing rootstocks from seed and subsequently grafting on ‘scions’ or short pieces of the desired plant. There are two advantages to this procedure, firstly the success rate is far higher and therefore more economical. Secondly, once the graft union has ‘taken’, the root stock will give rise to vigorous development by providing a good supply of water and nutrients to the scion so it can rapidly grow and develop

My Sister Ann, who made her career in the horticultural trade, told me how Dad used an innovative method of performing this operation for the Trinity Birch. His approach was more economical than methods formerly used in the industry, because the whole procedure could be accomplished without the expense of either specialist facilities or the use of heat.

First Dad grew, from seed, a batch of native birch and established them in pots, until their stems were of pencil thickness. Then, in late January he dried the plants off by ceasing to water them which arrested the flow of sap from the roots. Too much sap at an early stage, can interfere with the binding of the scion to the stock.

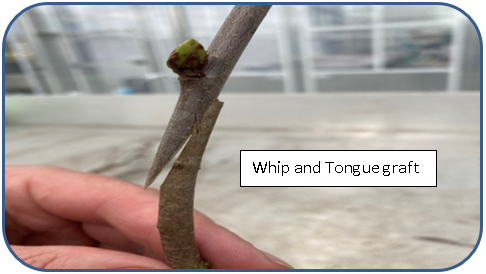

When the stocks were dried to his satisfaction, he lopped off their tops using a secateurs or knife to make a slanted cut. Then the bottom of the scion material was sliced at a matching angle. Matching the thickness of both stock and scion insures that the cambium layers align. This layer, that lies between the interior wood and the external bark, ensures a conduit is formed for water and nutrients to move from the roots up through the plant. The success of a graft primarily depends on ensuring these layers match together.

Once stock and scion was properly aligned, the graft site was secured using a rubber tie and then everything above root level was dipped into melted paraffin wax. When the wax cooled, the graft site was sealed so the union would not dry out until it had ‘taken’. And it also prevented infection from surrounding soil microbes.

The newly grafted plants were then lined out on a bench in an unheated greenhouse. When the scions began to sprout, the paraffin wax cracked and flaked away and gradually, a normal watering regime was re-established to facilitate the growth and development of the young tree. In the case of the Trinity Birch, Dad managed to cultivate an established a tree, suitable for commercial sale within 3 years of sowing the understock seed, all done, as was his wont, with minimal resources and maximum yield.

During the 1960s, Dad had solved a number of similar tricky propagation problems at Kinsealy. All this was done while he was also running the family rose growing business which I discussed in the last episode. But, by the early 70s, the bottom had fallen out of the rose trade which had provided a nice supplementary income to the family. My Mom, being more commercially minded, suggested transitioning to a nursery, leveraging Dad’s propagation skills in growing a broad range of plants. These plants would then be sold to retail garden centers which were emerging around Ireland.

When starting a new venture, it can be difficult to decide on a product line. Given the number of alternative plants that can be sold commercially, it’s important to select plants that have commercial appeal. It seems that Dad’s job at the Kinsealy Institute might have become a good conduit for gauging demand as calls would frequently be made to his department seeking to identify a source for a plant in short supply. In the early 70s, it seems there was a demand for fast growing hedging and one tree fit that bill perfectly, the “accursed” Leyland Cypress.

Why accursed? There is nothing particularly bad or evil about Leylands, as a matter of fact they have the singular virtue of being able to grow three to four feet a year in a variety of soils. In a blustery climate, like Ireland, they make for an excellent wind break, so why curse such a virtuous grower? Simply because they require a lot of maintenance which few can afford. When properly clipped they can make a wonderful dense evergreen hedge, however, if left to their own devices, they turn into a straggly, ugly, bare bottomed tree and it is this look that is far more prevalent and is a blight on many places in the Irish landscape.

Ugly wind breaks, however, were a thing of the future, when my parents set out to produce Leylands by the hundreds and then thousands. Dad sourced the propagation material which he passed to Mom who dipped the cuttings into a special hormonal rooting powder and then planted in trays containing a mixture of sand and peat. These trays were then placed in a custom built propagation glasshouse which contained raised benches one of which was rigged with an automatic misting unit which kept the Leyland cuttings moist as they rooted in their warm setting.

I assume Dad had implemented a similar misting system at his job in the Kinsealy Institute, however his ability to rig these kind of setups always impressed me and I was fascinated by the automation involved which utilized an artificial leaf. The leaf, looked nothing like any kind of vegetation, it was simply a rubber cylindrical sensor which was hooked up to a water pump and when dry, would trigger the sprayers to mist until it’s surface became wet again. I took great pleasure in triggering the mist by blowing on the leaf surface so that it dried. It seemed magical to my mind and impressed visiting childhood friends.

Once the Leyland cuttings were rooted, they were individually potted into small plastic pots and returned to a dry, non misting bench in the warmth of the glasshouse so that they and their root system could mature. In a prior era they would then have been planted outdoors to grow to saleable size, but things were changing in commercial horticulture. Traditionally plants were sold bare root, meaning that when they reached saleable size they would be dug up in the cooler months during the dormant phase of their growth and then sold for planting in Spring.

The old ways changed with containerization, which is just a fancy term for growing plants in pots. Now pots are nothing new to humanity, they’ve been around as long as the ancient civilizations of Rome, Greece and Egypt who used pots to transport, cultivate and display plants. These ceramic containers of times past, have multiple virtues for the gardener, simple beauty and water permeability jump to mind, however they are heavy and expensive, neither property being virtuous from a commercial grower’s perspective.

Some time in the late 60s or early 70s, plastic sleeve pots became available. They were cheap, light, easy to handle and took up little storage space. This seemingly innocuous invention revolutionized growing, producers no longer needed good ground for cultivation, they could simply mix up different potting soils depending on the plant and grow right in the container. Nor did they need to lift plants during the Winter months, for sale in the Spring. Plants could now be sold and planted late in the growing season as their transfer from pot to ground caused minimal growth disruption unlike the old bare root way of doing things.

Dad and Mom went all in on this containerized plant production revolution. My childhood and that of my siblings was dominated by the potting of plants in an old shed hastily acquired as the nursery business expanded. While potting plants in plastic sleeves decreased and eased handling costs and difficulty, the actual potting potting itself was tricky given the non rigid nature of the containers. The key to success, in using these sleeves, required packing the pot enough with soil in the bottom corner folds of the floppy container so that it could stand up like a rigid pot, but not so much that it would inhibit the growth of the plant roots. It was a skill every member of the family learned and if called on to do it today, it’s so deeply burnt in, that I expect I could still execute perfectly 40 years on.

In addition to the propagation glasshouse, Dad erected plastic tunnels whose warmth sped up the early growth of plants towards salable size. In the final phase of production, plants were transferred to the outdoors so that they could adjust to the cooler Irish conditions from the warmth of the tunnels. In this last phase, the plants were placed on capillary beds made up of moist sand fed by a water pump. The pots were screwed down into the damp sand so that water would feed up through the hole at the bottom of the pot. This clever system greatly reduced the amount of time spent watering and was consistent with Dad’s labor saving ethos.

While this infrastructure was being built out, the offerings of the nursery expanded from Leylands. Dad had already been bitten by the collapse of the rose business and likely never wanted to experience a similar heartbreak of ploughing a crop into the ground when market demand collapsed. And so, a diversity of plants were grown beyond Leylands, with a particular effort to grow the unusual and/or difficult to propagate. I imagine that Dad used his job at the Kinsealy Insititute as a test bed in propagating plants that were difficult to cultivate. When he cracked a problem plant, which he thought commercially viable, he made it an offering in the growing nursery

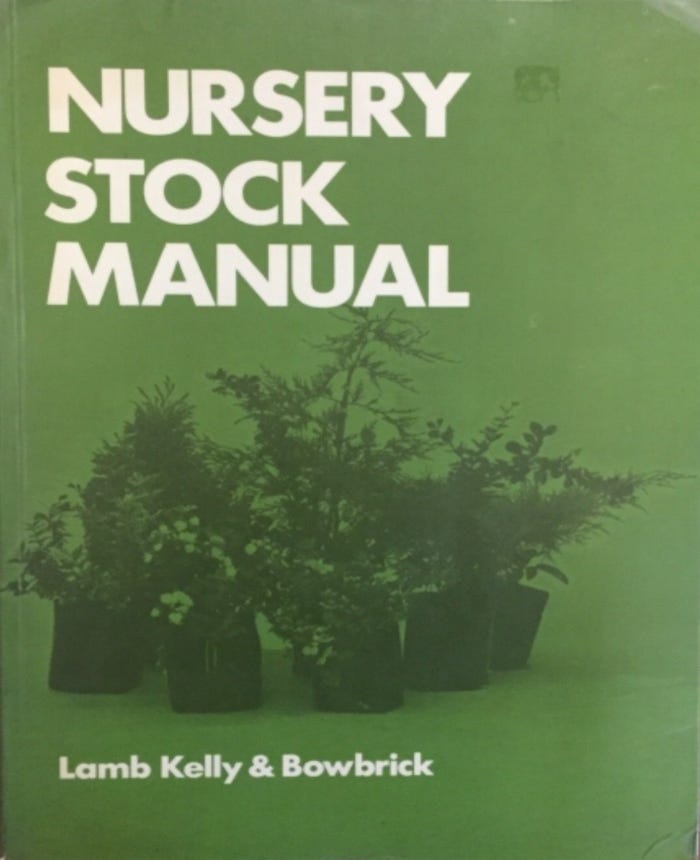

How all this private commercial activity fit with Dad’s main job is a matter of speculation. My sister Ann related how a certain colleague from Kinsealy had remarked that Dad might be “sailing a little close to the wind” in his private endeavors. It’s likely, there was a prohibition on moonlighting at the Institute, which makes me wonder as to how he evaded censure. The truth was, Dad’s employment in Kinsealy was a source of aggravation to him. Despite his innovative work, his lack of a college degree restricted his advancement. In 1975, Kinsealy published the Nursery Stock Manual which to this day, is a much cited and referenced work in the trade. The book contains much of Dad’s work and yet his name did not appear on the cover, the absence of academic credentials precluded recognition in this publication and others. This lack of acknowledgement spilled over into periodic bouts of bitterness which would manifest itself at the family table.

Given the emerging success of the family nursery business, one could ask why he chose to remain at Kinsealy? The Ireland of the 70s was a very different place, entrepreneurial types were not lionized and more importantly, now modern Irish talent does not have a fixation on the retention of pensionable employment. The economic difficulties and limited opportunity faced by Dad in his early adulthood in the 1940s and 50s bred a mindset averse to risk and so he remained at Kinsealy while other family members and I were treated to daily denunciations of those who appropriated his work.

I often wondered, whether Dad verbalized his dissatisfaction on the jobsite at Kinsealy or were we, his family, the sole beneficiaries of his bitterness? One thing was clear to me, despite his government job, he didn’t adhere to a rigid working day schedule. His daily lunch hour would frequently be extended, when he returned home for a quick meal and then headed outside to pursue other interests on the family property. His 9AM start time was also treated in a cavalier fashion which still makes me speculate as to why his lax attitude was tolerated by his superiors? Was the Kinsealy work environment permissive of tardiness or was Dad some kind of golden goose, not to be interfered with. A man who produced innovative ideas which could be turned into kudos winning publications by types with the right academic credentials? Those that know the answer, are almost all gone now and the mystery will remain.

When I visit my Mabestown home and look out my Mom’s kitchen window, I see a glossy, curly, purple leaved plant. It’s a pittosporum, a family of plants which originated from New Zealand. However, this one is special to my family and I, as its called: Pittosporum tenuifolium ‘Nutty’s Leprechaun’. It is a small legacy to the world of horticulture that reminds of Dad’s contribution to the field. There is also a Mabestown Aubretia, which he also named, a small easily missed, ground hugging plant which produces pretty blue flowers with a white heart.

For me though, there will always be the Trinity Birch, one of which stands outside Dad’s workshop. The tree with the gleaming white bark does not bear his name, but my family and I know how instrumental he was in it’s preservation. Somehow it connects and reminds of all those things that were special to him, the beauty of the unusual, the importance of things natural and a connection to a time past when curiosity was valued in gaining a deeper knowledge of the fragile world that we live in.

I like to think this tree and the other progeny of the beautiful birch grown from Hooker’s seed, connects me and my family to Darwin in a deeper and intimate way across time, a smaller set of degrees of separation, so to speak. I know such thoughts are fanciful and foolish, but they are both my family’s and mine and are cherished. Dad is gone, 9 years now, he was an unusual and imperfect man that I still struggle to understand. There are vestiges of him in me that are undeniable, things that I sometimes find unpalatable about myself and other things that are satisfying. I catch myself wondering at times, if these traits are inheritance playing out in a way that would make Darwin smile. Dad’s ashes are buried beneath a Trinity Birch, there is no stone detailing his dates, just a tree, a living monument to a man driven by curiosity and a thirst for knowledge. I will not see his like again.

Credits:

With thanks to my Sister Ann whose knowledge of all things horticulture, including grafting, rivals our Dad. Ann is now a Cistercian sister known as Sister Fiachra in St Mary’s Abbey in Glencairn Co.Waterford. Thanks to my niece Rosa Nutty whose music is featured in this and many other episodes of The Nutty Chronicles. Also thanks to Tegasc and the Trinity Botanic Garden whose websites provided important information featured in this episode. I’m Martin Nutty and you’ve been listening to The Nutty Chronicles